Netflix has produced yet another dietary propaganda film designed to deceive the public.

It is based on a flawed study by a biased and corrupt researcher.

They're not exactly trying to conceal this either.

This is my Weekly Memo with few points on health and peak performance. Subscribe for free to receive weekly posts and support my work.

The "Game Changers" movie, released in 2018, was already a topic of debate. It pushed for veganism using a variety of arguments, cherry-pick data and was backed by the plant-based food industry. Despite this, it at least tried to present some truths and sparked discussions.

In contrast, “You Are What You Eat: A Twin Experiment” focuses solely on a single study from the Stanford School of Medicine.

This TV mini-series debuted on January 1, closely following the study's publication in an open-access journal on November 30. As the series tracks the titular twins, it's apparent that the creators had a specific message in mind from the start.

Indeed, the study's results are being celebrated in the vegan community, highlighting the benefits of a plant-based diet compared to an omnivorous one.

It's already making waves in the headlines.

Twin Vegan Study Flawed Science

I'm going to focus more on the study than the show here, because trying to cover everything from the series would make this way too long.

But no worries, the show is still a big part of what we're talking about.

So, let's take a look at the study itself. It's supposed to be the backbone of the show's credibility. The twin study was led by Christopher Gardner, a professor at Stanford University.

The study aimed to measure how a healthy vegan diet compares to a well-balanced omnivore diet (which includes both plant and animal foods) in terms of the risk of heart disease.

It was a randomized controlled trial (RCT) — basically the gold standard for research in nutrition and medicine. The trial ran for 8 weeks, which, honestly, is pretty brief for judging the long-term impact of any dietary change on health. But RCTs are expensive and difficult to do. Even within this short window, we can get a sneak peek at how diet tweaks can affect our bodies.

For the first 4 weeks of the study, participants were given meals specific to their assigned diets. Then, for the next 4 weeks, they had to cook their own meals, but they had to stick to certain diet guidelines.

The main outcome they were looking at was the difference in LDL-C (the so-called “bad cholesterol”) between the two groups after 8 weeks. They also checked out other cardiovascular health markers like fasting insulin levels and body weight as secondary outcomes.

At the end of the 8 weeks, the vegan group showed a pretty noticeable drop in their LDL-C levels compared to the omnivores. Plus, the vegans tended to lose more weight.

Based on these results, Gardner concluded that a vegan diet is better for heart and metabolic health than an omnivorous diet.

Seems okay on the surface. But let's dive into the details and see what's really going on.

It's true that the vegans in the study had lower LDL-C, fasting insulin, and body weight.

However, Gardner kind of glossed over that the vegans also had lower HDL-C (the "good cholesterol") and higher triglycerides. These points didn't get much attention in the discussion, even though they're may be even more important markers for heart disease.

Gardner's Approach Could Be Seen As A Classic Case Of Cherry-Picking Data.

Gardner deliberately focused on the LDL-C, which is well-known to be lowered by the vegan diet, so he probably expected this result from the beginning. But, he ignored other important markers, and the overall changes in lipid profiles for both groups were kind of mixed.

Here's an interesting bit: the ratio of total cholesterol to HDL-C, a key factor in heart disease risk where lower is better, actually improved slightly in both groups – it went from 2.8 to 2.7 in vegans, and from 2.9 to 2.8 in omnivores. This hints that maybe both diets have beneficial effect. But Gardner did not include this in his paper.

Gardner chose to spotlight just LDL-C as the main marker for heart health to prove his point.

There's a catch with his argument, though. Sure, a vegan diet can really cut down cholesterol levels, especially LDL-C (other studies back this up), but that's mainly because of less saturated fat and more plant sterols in the diet.

And this is not necessarily all good news.

Is Cholesterol Really That Bad?

Cholesterol is vital for all animal life, including humans. It’s a key component of cell membranes and serves as the building block for hormones like testosterone and estrogen. It is essential for vitamin D production. It protects your nerve fibres and allows nerve signals to be transmitted. In fact, our brain loves cholesterol as it contains 25% of all the cholesterol in the body.

Dietary cholesterol intake has little effect on the total cholesterol in your blood. Your body produces enough cholesterol to meet your needs.

LDL and HDL are lipoproteins, which are responsible for transporting cholesterol around your body. LDL, often labeled as “bad,” carries cholesterol to body tissues. HDL, known as “good,” moves cholesterol from tissues back to the liver, where it's either reused or expelled from the body.

Phytosterols, found in plants, can kind of take over the job of cholesterol made by our bodies. That's how eating plant foods can lower the levels of LDL and HDL in your blood. These plant sterols compete with the cholesterol we produce and replace it to an extent.

But here's the thing: there's no solid evidence that plant sterols actually reduce the risk of heart disease. In fact, there's a lot of evidence suggesting that they can be harmful. Several studies have shown that despite their cholesterol-lowering effect, plant sterols are associated with an increased risk of CVD and cancer, especially in men.

The goal is to improve health and reduce the prevalence of disease, not just to lower specific marker levels.

On top of that, the cholesterol hypothesis as a major cause of CVD is currently being challenged by several studies that have produced conflicting results.

For example, one study with almost 140,000 heart attack patients found they had lower than normal LDL-C levels. Another, involving over 115,000 participants, observed that higher LDL-C was associated with longer lifespans. This debate about cholesterol and heart disease is a complex and evolving topic.

They Just Ate Less

The twin study also noted that vegans lost more weight, which is typically a positive. But it turns out this might be because they consumed about 180 calories less each day than the omnivores. Plus, the omnivore diet had more sugar and less fiber.

This lower calorie intake among vegans led to their greater weight loss.

Weight loss is known to help improve your lipid profile and fasting glucose levels. So, it's not really fair to say that the improvements in these cardiometabolic markers were solely due to the vegan diet. It's also interesting to mention that the vegans might have eaten less because they reported being less satisfied with their food compared to the omnivores.

Outcome Switching To The Rescue

In the U.S., if you're running a randomized controlled trial (RCT), you've got to send your clinical trial protocol to the National Institute of Health before you start. This includes detailing the specific outcomes you're planning to measure.

Turns out, the outcomes Gardner reported in his paper weren't the ones listed in his trial protocol.

He changed them after study was done, adding fasting insulin and body weight, which helped him make the case for the vegan diet. But other outcomes, which were initially part of his protocol, didn't make it into his final paper.

This practice is known as "outcome switching" and it's widely disapproved of in the scientific community. Changing your experiment after seeing the results introduces bias and undermines the integrity of the study.

Gardner tweaked the outcomes he focused on to better support his argument, which is a bit of a scientific no-no.

Give Me Hypothesis, Enough “Resources”, And I Will Prove Your Point With “Science”

It's not exactly breaking news that a lot of studies get funding from industries that could benefit from the results. This happens across various sectors – pharma, meat, dairy, tobacco, and yes, even the vegan or plant-based food industry.

The plant-based food market has been skyrocketing.

What used to be a pretty niche market just a decade ago, has exploded into a $29.4 billion industry by 2020. Bloomberg predicts it will quadruple to over $160 billion by the end of the decade.

Clearly, there is a lot of money to be made.

Biased To Its Core

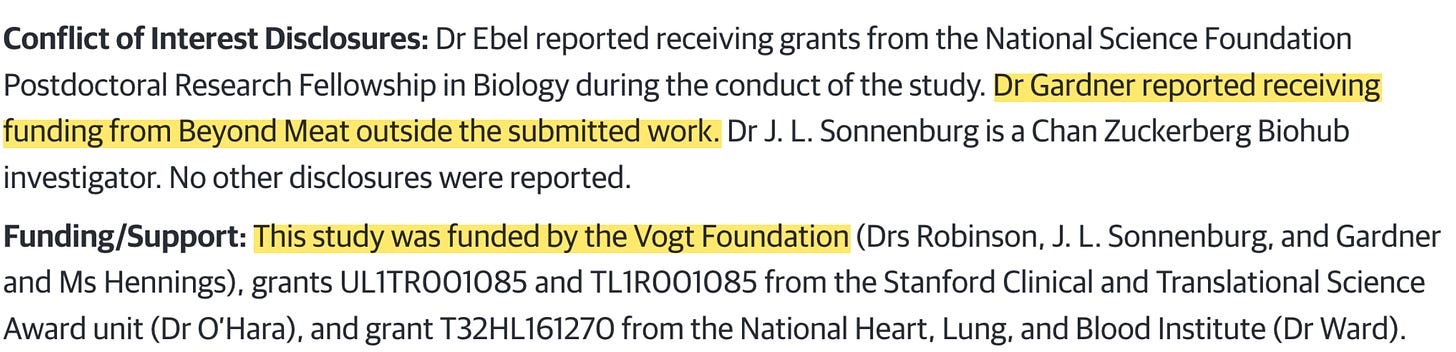

When you peek at the funding sources and declared conflicts of interest for the twin study, some interesting points emerge:

Gardner, the lead researcher, received funding from Beyond Meat, a major player in the plant-based meat industry. This funding was reportedly separate from the twin study.

The study itself was funded by the Vogt Foundation.

In 2021, Beyond Meat, a leading company in the plant-based food sector known for meat substitutes, launched the Stanford Plant-Based Diet Initiative (PBDI). They pledged substantial funding for five years to support “peer-reviewed, clinically-significant studies on the health implications of a plant-based diet”.

The director of the PBDI just so happens to be none other than Gardner. Although he says in the paper that Beyond Meat did not directly fund the twin study, it was carried out a year after PBDI was set up.

These connections raise some questions about Gardner's objectivity as a medical academic.

He's been a vegetarian for over 25 years and openly acknowledges that his food research is influenced by factors beyond health, like environmental concerns, animal welfare, and human labor issues. As a medical scientist and nutrition researcher, one might expect his primary focus to be on enhancing and optimizing human health.

Oh, and it's worth mentioning that Gardner is involved with the American Heart Association, where he chairs the Nutrition Committee, which sets dietary guidelines for Americans.

We would naturally expect prestigious organizations like the Stanford School of Medicine to carry out nutrition research free from personal beliefs, societal issues, and other factors unrelated to health.

Climate change is undeniably important. However, such issues shouldn't influence the outcome of studies focused on the health effects of diet.

These environmental and societal concerns are certainly relevant in broader policy discussions, but when it comes to scientific research, especially in the field of nutrition, the primary goal should be to gather the most objective data possible. This way, we can make well-informed decisions and educate people about the benefits and drawbacks of various diets.

In this case, it really does seem like science is being used as a tool to back up a specific idea that someone has already had, rather than being used to honestly find out what's true.

This kind of approach, where research is bent to support a particular point of view, really calls into question how much we can trust the results and science in general.

Vegan Mafia Doing a PR Stunt

The Vogt Foundation, established by Kyle Vogt, a member of the so-called “vegan mafia,” is deeply invested in the plant-based food market. This group, comprising investors and venture capitalists, focuses on sustainability and minimizing environmental impact.

The Vogt Foundation is known for backing plant-based projects.

It put over $1.0 million into Netflix's "Game Changers" movie, which promoted veganism but drew criticism for its somewhat misleading info and selective study choices. They're also regular supporters of other plant-based initiatives, like The Good Food Institute, which is all about pushing alternative protein sources.

Vogt Foundation funded Netflix's series “You Are What You Eat: A Twin Experiment” through OPS Productions.

We have already established that the Vogt Foundation funded Gardner's twin study, as clearly stated in the paper.

In conclusion:

The Stanford Twin Study, led by Dr. Gardner, a known advocate for plant-based diets, was influenced by factors beyond health, such as environmental and animal welfare concerns.

Gardner's focus in the study was mainly on LDL-C, while other important markers like HDL-C and triglycerides were overlooked.

He designed the experiment knowing well that plant sterols lower LDL-C. However, he ignored evidence suggesting this doesn't necessarily translate to better heart health and might even be harmful.

After the study, Gardner altered the measured outcomes to strengthen his argument in favor of plant-based diets.

Gardner disregarded other factors in the study, such as the lower calorie intake of vegans leading to weight loss, which is closely linked to improved lipid profiles and overall health.

The study and the Netflix series “You Are What You Eat: A Twin Experiment,” which showcases the study, were funded by the Vogt Foundation.

The same foundation previously backed “Game Changers,” a film criticized for promoting veganism using misleading information and questionable science.

Kyle Vogt, the founder of the Vogt Foundation, is a key member in the “vegan mafia,” investing heavily in plant-based food ventures like Beyond Meat.

Beyond Meat financed the Stanford Plant-Based Diet Initiative, directed by Gardner himself.

The Study And The Show Are One Big PR Stunt

And guess what? It works!

We will see how the show goes. If they push the vegan agenda too hard, there's a chance the internet and media might scrutinise and debunk their claims. But to be honest, I doubt it.

It looks like the study was crafted specifically for its Netflix showcase. And Netflix cares about views, not science. Netflix is a business, so I can understand that.

It's just a shame that scientists, who are supposed to maintain integrity and deliver unbiased results, get caught up in this mix of business and ideological propaganda.

DISCLAIMER: I am not against a plant-based diet. I am against the misuse of science to mislead people about such critical issues as health.